How United Is Belarus Against the Regime?

Belarus has undergone a pivotal year. Under the world’s gaze, mass protests swept the country after the presidential election in August 2020. Worldwide empathy with Belarus became apparent in numerous events and statements to mark a Day of Solidarity with the country on 7 February 2021. In addition, the Covid-19 pandemic has hit Belarus severely, and the country’s structural economic weaknesses are contributing to declining living standards. Trust in political institutions is low, and the population has no confidence that the regime can address its concerns.

To find out what Belarusians think after months of protests, the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) conducted an online survey in December 2020 among 2,000 Belarusians aged 16–64 living in towns and cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants. Quota sampling reflected the underlying population structure in terms of gender, age, and place of residence.

Consensus on electoral fraud

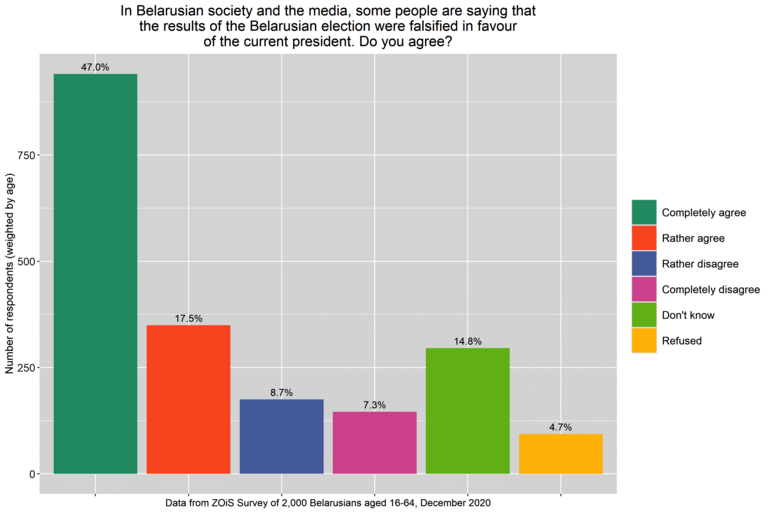

In the August election, Belarusian president Aliaksandr Lukashenka was returned to office with 80 per cent of the vote, according to official figures. However, 65 per cent of Belarusians surveyed partly or completely agreed that the result had been falsified in favour of the incumbent (figure 1). An OSCE report published in November 2020 confirmed that the election suffered from ‘evident shortcomings’ and underlined that human rights abuses were ‘massive and systematic and proven beyond doubt’.

Figure 1: Belarusians’ opinions on fraud in the 2020 presidential election

Of the respondents in the survey, 18 per cent reported having voted for Lukashenka and 53 per cent for the opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. The remaining respondents refused to answer the question or said they had spoiled their ballot. These latter responses might reflect participants’ concerns about their safety.

Mass protests have been a defining feature of recent months. At the height of the demonstrations in August, observers reported that there were nearly 1 million people on the streets of Belarus. In December, half of the survey respondents said that they knew someone who had been protesting. This is a significant increase. An earlier ZOiS survey in June and July 2020 found that only 20 per cent of people aged 18–34 knew any protesters.

In the latest survey, 14 per cent of respondents said they had protested since the election. On a national scale, that represents around 700,000 Belarusians aged 16–64. Participants’ reasons for protesting varied, but shock at state violence towards protesters was the most frequently mentioned factor. Indeed, 20 per cent of respondents said that they, their family members, or their friends had been affected by state violence, underlining the extremely low levels of trust in the country’s institutions at the end of 2020.

A fractured society?

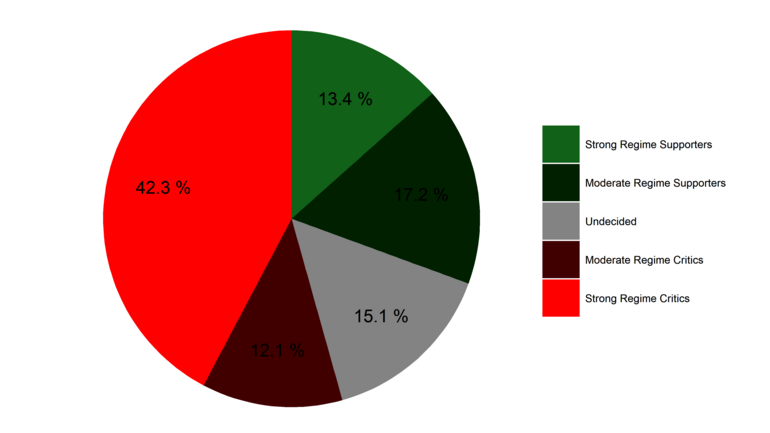

After a stolen election and large-scale protests, what are Belarusians’ perspectives on their country’s political situation? Based on their answers to fourteen politically salient survey questions, respondents were classified as either strong regime supporters, moderate regime supporters, undecided, moderate regime critics, or strong regime critics. For every respondent a value on each of these five scales was calculated and respondents were then attributed to the most frequently chosen category. An analysis of the correlations confirms the consistency of the categories, but it should be noted that people may hold contradictory views.

The categories reflect, among other factors, respondents’ trust in the president or the opposition Coordination Council, vote choice, and views on the protests, state violence, and how the crisis should be resolved.

According to this scheme, 42 per cent of respondents were strong critics of the regime—by far the largest group (figure 2). At the other end of the spectrum, 13 per cent were strong supporters of the regime and 17 per cent expressed moderate support.

Figure 2: Attitudes towards the regime in Belarus

In terms of the characteristics that determine a person’s level of support for the regime, age plays only a minor role: people in their thirties are more likely to be undecided or moderate regime critics, but there is no systematic relationship as there is with categories such as education, gender, and place of residence.

Being a student turns out to be a critical factor. Students are almost 40 per cent more likely than non-students to be strong critics of the regime and 60 per cent less likely to strongly support it. Indeed, universities are key venues for the expression of criticism of the regime. Moreover, respondents with higher levels of education were significantly more likely to be strongly critical of the regime, whereas lower levels of education correlated with higher levels of both supporting the regime and being undecided.

Gender and settlement size correlated systematically with views on the regime. Male respondents were significantly more critical of the regime, as were those living in larger cities. The effect of gender is remarkable, because observers have cited the mobilisation of women as an important element in bringing about a durable transformation in Belarusian society, irrespective of the political outcome. Traditionally, female participation in informal politics has been significantly lower than male involvement.

Religion is an important influencing factor as well. Lukashenka’s supporters are more likely to be Orthodox, whereas Protestants and Catholics are more likely to be critical, reflecting the positions taken by these denominations during the protests.

A final notable aspect is that strong critics of the regime also said their societal trust had increased over the past six months. It is beyond doubt that the protests brought different sets of people together and gave them a more confident outlook towards their peers. Strong regime supporters, meanwhile, report declining levels of societal trust.

Where next?

The new data underline how profound the gulf is between Belarus’s population and the country’s political leadership, and how many people—beyond those who take their discontent onto the street—feel disconnected from the political class. But also the opposition needs to unite the diverse population—being critical of the regime does not imply support for Tsikhanouskaya. Even if the regime lacks popular support and has no vision for how to regain support among educated urban Belarusians, there is no guarantee that it will crumble in the foreseeable future. Therefore, the stalemate of harsh repression and the president’s refusal to engage in any dialogue with Belarusian society may continue for some time.

Félix Krawatzek is a senior researcher at ZOiS. The survey this text is based on was conducted as part of the project ‘Belarus at the Crossroads? Public Attitudes after the 2020 Election’.