Memory laws and Polish voices from abroad

In February 2018, the Polish government passed a law that made it a criminal offence to accuse the Polish nation of complicity in the Holocaust and to speak about ‘Polish death camps’. The reform of the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance caused an international outcry. The legislation was criticised not only for threatening free speech and being an act of historical revisionism but also for being largely unenforceable.

The law forms part of the country’s uneasy relationship with Holocaust history and a sustained effort by the Polish leadership to interfere with the independent research of academics. Israel in particular felt that the law ‘was a betrayal of the memory of the Holocaust’, as Yehuda Bauer, professor emeritus of history and Holocaust studies at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, put it.

The law was eventually modified in June 2018, when the criminal clause was removed after a meeting between the prime ministers of Israel and Poland. Benjamin Netanyahu and Mateusz Morawiecki issued a joint statement emphasising the ‘common responsibility to conduct free research, to promote understanding and to preserve the memory of the history of the Holocaust’ and acknowledging and condemning ‘every single case of cruelty against Jews perpetrated by Poles during the World War II’.

One aspect that has received little attention in the context of the law and its modification is the transnational dimension. This perspective illustrates the importance that migrants and their descendants can play for political developments in places of origin and residence.[1]

The mobilisation of Poles abroad, either for or against the law, is a noteworthy example of political remittances. Polish media have referred to the support of the Polish diaspora, for instance in the US and Canada, for the government–affiliated Institute of National Remembrance’s (IPN) position. The national media amply quote Polish-Americans who are outraged about the criticisms against Poland to prove the reform is needed to ‘defend the truth’.

In February 2018, the chairman of the Polish Senate, Stanisław Karczewski, tried to rally Poles abroad to defend the law. In his letter, he emphasised the Polish diaspora’s long history of supporting Poland. His letter also reacted to the growing international criticism, in particular from Israel. There, survivors of the Holocaust and their descendants demonstrated throughout February at the Polish embassy in Tel Aviv. Slogans in Polish and Hebrew evoked the demonstrators’ personal stories of suffering and mistreatment by Poles during the war.

The Polish memory law is a critical event that reactivates the links between those who live outside Poland and their country of origin. Such moments of upheaval have particularly led to increases in political remittances.

Identifying political remittances

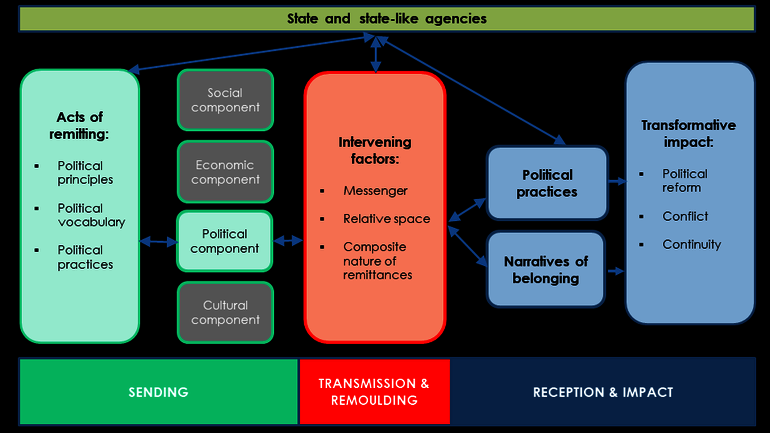

Beyond the controversy that such memory laws generate, how should one approach transnational activism, its origin, its transmission, and its potential impact? Political remittances are identified as ‘the act of transferring political principles, vocabulary and practices between two or more places, which migrants and their descendants share a connection with’. The following figure shows the flow and transformation of political remittances between their origin and destination:

In the case of the Polish memory law, a focus on political remittances would include transfers between Poland and Polish migrants of norms and ideals (principles), symbols or slogans (vocabulary), and forms of mobilisation (practices).

A look at mobilised conservative groups in Chicago illustrates these dimensions. The city has been a hub for Polish migrants since the nineteenth century and has one of the highest shares of Poles in the US. Trucks with the hashtags #GermanDeathCamps and #ReparationsForPoland drove across Chicago in support of the Polish government’s historical position. The series of events was organised by a right-wing group in the US, the Chicago branch of the Chicago branch of a national Polish association of veterans (Związek Żołnierzy Narodowych Sił Zbrojnych). The Polish-American activists demanded compensation for war damages, using the symbols, imagery and hashtags that the IPN generated. Right-wing Polish media were positive in their coverage of the truck convoy as a practice of mobilisation.

The local context is of great importance for understanding political remittances. Regarding the Polish memory law, Chicago and Tel Aviv are particularly salient places given the previous migration patterns in both places. In both cities, mobilisation is embedded in historically grown networks, which accounts for the type of remittances and their flow.

Indeed, political remittances are frequently grass-roots phenomena initiated by ordinary citizens. In this regard, the characteristics of the messenger—the Polish networks in the US or Israel—are a determining factor. Both groups convey their messages in the language of their place of origin. The website of the Polish-American organisation is even exclusively in Polish.

Moreover, the Polish-American veteran organisation, which is strongly anti-communist and Polish-nationalist, amplifies a conservative interpretation of history in tune with that of the current government and a significant part of Polish media and civil society. Conversely, the Polish-Israeli mobilisation was carried out by the politically left-wing diaspora in Tel Aviv, which reflects the global norm of cosmopolitan Holocaust memory. The latter group consists of an older generation, which does not have the strong affective bonds to Poland that characterise the Polish-American networks.

Why political remittances matter

Through diaspora policies and direct calls to its population abroad, the Polish state and its agencies play an important role in influencing remittances. The direct target of the mobilisations discussed above was the state, which was either under attack or supported. Channelled by the media, the support of Poles abroad contributed to legitimising the reform of the memory law.

At the same time, the Polish government could not contain the international criticism of Poles abroad. Given the widespread international condemnation of the legislation, the government eventually needed to modify some aspects of it, notably the controversial criminal clause.

[1] In a special issue of the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies entitled Political Remittances and Political Transnationalism: Practices, Narratives of Belonging and the Role of the State, Lea Müller-Funk and I develop the concept of political remittances further.

Félix Krawatzek is senior researcher at ZOiS. One of his research projects centres on the proliferation of memory laws and the return of the nation.