Evacuation Decisions: Lessons from Russia’s War against Ukraine

A new survey of Ukrainians in Ukraine shows that an awareness of the risks associated with Russia’s war does not automatically lead people to evacuate. This has important implications for the framing of evacuation messages. Messages that contain clear evacuation instructions are more likely to be followed.

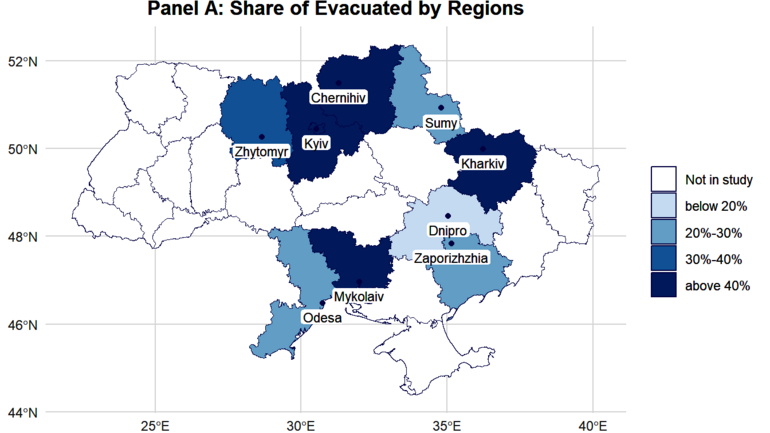

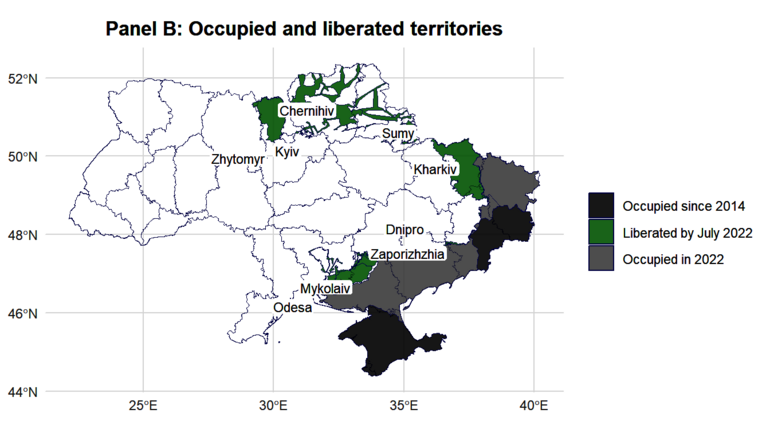

Despite numerous media reports of a possible invasion, only 28 per cent of Ukrainians anticipated the Russian attack in February 2022. A mere 15 per cent had a rough plan before 24 February for where to go in an emergency. However, the rapid military escalation and the extensive scale of the attack forced 38 per cent of Ukraine’s population to leave their homes during the first five months of the war. These are among the findings of a representative survey of around 2,000 respondents from cities with populations of over 50,000, conducted by the Institute of Behavioral Studies at the American University Kyiv in July 2022 across the ten Ukrainian regions most affected by the war (figures 1 and 2). The respondents were a mix of people who evacuated and people who chose to stay.

Perceptions of risk

In spite of the evident dangers of the war, many people remained in their homes. The first and most apparent factors that influenced the decision to stay or leave are socio-demographic. Women, married people, and families with children tended to evacuate more than other groups. People with a higher education, those with a greater income, and car owners were also more likely to leave. Conversely, older people and those with larger families were more prone to stay.

Initially, it was assumed that the decision to evacuate would be influenced by individuals’ perceptions of risks, a theory derived from studies on natural disaster evacuations. Those studies suggest that if a person does not perceive a situation as dangerous, they are unlikely to leave. However, the findings of the Ukrainian survey presented a different picture. Respondents were asked to estimate the likelihood of each of the following scenarios of what might happen if they stayed in their city:

- I or one of my relatives could be killed or seriously injured.

- Illegal acts such as violence, rape, or robbery could be committed against me or my family.

- I would face problems with food, drinking water, or medicine.

- I would face a lack of electricity, water, or gas.

- I could be under occupation due to the transfer of my city to the Russian army or the armies of the Russian-backed separatists.

- I could be injured or killed as a result of the destruction of or damage to my house.

Contrary to the initial assumption, it became evident that the respondents were well aware of the high risks associated with military action (table 1). There is no evidence to suggest that this awareness was consistently more pronounced among respondents who had evacuated. It is true that they evaluated the risk of death or injury higher than other respondents. But other risks, like the destruction of one’s house, were more salient for those who stayed. And both groups rated the risk of violence or robbery similarly. All of this indicates that risk perception was not a significant factor in people’s decisions to stay or leave.

These findings imply that to convince people to move to safer places, it is ineffective to emphasise the dangers of staying put: people are already aware of these dangers. The survey included an experiment in which respondents evaluated the effectiveness of ten evacuation messages, each of which had a different motivational framing, either with or without a specific evacuation plan. Each respondent received one message, which they rated on a scale from 0 to 10.

It was found that the message’s motivational framing did not significantly impact its effectiveness. This finding corroborates the notion that people understand the dangers well and thus do not require further external motivation. However, the inclusion of a practical evacuation plan made a statistically significant difference, raising the average effectiveness rating from 6.5 to 7.25.

The importance of making plans

This focus on the importance of planning is further highlighted by the behaviours of those who actually evacuated. Among the respondents who had their own preliminary evacuation plan before the invasion, 59 per cent left their city, compared with just 36 per cent of those without a prior plan. Although this could be a case of self-selection, whereby those predisposed to move had made plans, it still seems that having a plan eases the decision-making process. Therefore, when attempting to evacuate individuals from war zones, it might be effective first to encourage them to make a plan and prepare their belongings and then, after a period, persuade them to depart. This approach may not be feasible in situations where a city is on the front line and under heavy shelling. Yet, this two-step strategy could be effective in areas where evacuation remains a viable option.

Thus, if governments, international organisations, NGOs, or volunteers are attempting to evacuate people from war zones and encounter hesitation, they should bear in mind a few points that might persuade some individuals to leave. Firstly, emphasising the dangers of staying is not helpful, as awareness of these dangers does not play a crucial role in many people’s decisions to evacuate. Instead, individuals need simple and clear evacuation instructions, including transport details, a list of essential items, contact points, and information about the assistance they will receive in the new location, such as medical support, accommodation, food, and financial aid. This information offers a minimum of planning security in an overall uncertain situation.

If the military environment allows, a two-step approach makes it easier for people to adjust to the thought of leaving: they should be given the opportunity to make arrangements, such as collecting documents and clothes, before agreeing on a date and time to be taken out of the danger zone. After all, the decision to leave one’s house and home is very difficult and has serious consequences for people’s lives.

Natalia Zaika works at the Institute for Behavioral Studies at the American University Kyiv and is a fellow at the Ukraine Research Network@ZOiS, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.